- The 2023 Annual Berkshire Hathaway Letter

- You Need to Be Open to a Big Pivot

- You Need to Have Some Money On Hand

- You Need to Know the Value of Dividends

- Wrapping Up Buffett's Three Big Lessons

Warren Buffett once admitted to a $200 billion blunder. One that is still as prominent as possible.

Back in 1962, he bought a US-based textile company. By 1967, Warren Buffett had started moving his money, far less than he has now by any metric, into insurance businesses.

By 1985 the last textile operations were shut down. Thus ended the original Berkshire Hathaway. In 2010, Buffett estimated it cost him $200 billion in compound interest and potential.

Yet Buffett's empire still bears the name.

Do you think he still ponders this blunder whenever he sees the name on the marquee? Could it almost be intentional?

With his candor with shareholders, I wouldn't bet against it. I don't think it is some kind of self-flagellation, either. It is what it is, something that happened along the way.

Warren Buffett has always been candid with his successes and failures. Sure, it's easy when you're practically deified for your track record, but a lifetime of integrity carries him into a unique category.

Nowhere else is this more apparent than in his annual dispatches, made public to shareholders.

From it we can distill a lifetime of lessons from his successes – easy to see – but also his blunders. Today, we will look at some of the latter in his own words.

The 2023 Annual Berkshire Hathaway Letter

A letter goes out to shareholders every year, but it's functionally a public document.

I'm sure a legal team and some internal marketing folks pick over it. But unlike an overly sanitized investor relations annual release from most companies, there is an almost editorialized component that I'd bet Warren Buffett himself has the last say on approving.

It's become one of the few ways he communicates with shareholders and the stock markets, almost like a “State of the Union” address from a president.

Here are a couple of quotes from the 2023 letter to shareholders that lays out the reality of his business:

First off, we have the structure of his business explained in simple terms:

“Charlie [Munger] and I allocate your savings at Berkshire between two related forms of ownership. First, we invest in businesses that we control, usually buying 100% of each. Berkshire directs capital allocation at these subsidiaries and selects the CEOs who make day-by-day operating decisions. When large enterprises are being managed, both trust and rules are essential.

In our second category of ownership, we buy publicly-traded stocks through which we passively own pieces of businesses. Holding these investments, we have no say in management.”

This is about structure, and Berkshire Hathaway is a hybrid investing company. It draws a clear line between what it can directly influence through management or board members and what it holds.

More telling is what Buffett states next:

“Over the years, I have made many mistakes. Consequently, our extensive collection of businesses currently consists of a few enterprises that have truly extraordinary economics, many that enjoy very good economic characteristics, and a large group that are marginal. Along the way, other businesses in which I have invested have died, their products unwanted by the public. Capitalism has two sides: The system creates an ever-growing pile of losers while concurrently delivering a gusher of improved goods and services. Schumpeter called this phenomenon “creative destruction.”

So what does Buffett cite as his blunders along the way? Here are several and what small investors can learn from them.

You Need to Be Open to a Big Pivot

As quoted from the 2023 shareholder letter:

“In 1965, Berkshire was a one-trick pony, the owner of a venerable – but doomed – New England textile operation. With that business on a death march, Berkshire needed an immediate fresh start. Looking back, I was slow to recognize the severity of its problems.

“And then came a stroke of good luck: National Indemnity became available in 1967, and we shifted our resources toward insurance and other non-textile operations.”

Buffett's investments changed dramatically, but the goal was the same. He was saddled with ownership of a shrinking textile business but was willing to take a big risk and pivot to an entirely different industry to pull in revenue.

It was a risk taken when the markets were very different. Insurance markets were growing, and it isn't like the NASDAQ, tech sector, or derivative markets existed. It was about as big of a pivot as possible in 1967. An owner of an old New England textile producer moving into purely financial services.

It was one of the most significant and riskiest leaps of Warren Buffett's career, but it is a lesson to learn to this day.

Buffett was looking for profit potential and cash flow, and while making textiles and selling insurance couldn't be more different, the ultimate goal was to make more money and reinvest in what works.

Another way to put it is that he saw his current company had no catalyst for growth and did not hesitate to capitalize on moving towards another that did. That is what we should learn.

The free cash flow from that pivot into expanding businesses funded a massive expansion in revenue and profits. The rest is history.

You Need to Have Some Money On Hand

Another part of this lesson about the early years is that Warren Buffett didn't always have money on hand.

He certainly didn't always have an endless list of bankers and investors willing to throw money at him. He barely bought an underfunded insurance company while owning a fading textile business.

That lesson has carried on for quite some time and has returned fantastic results over the years for Berkshire Hathaway.

As stated in the annual letter:

“As for the future, Berkshire will always hold a boatload of cash and U.S. Treasury bills along with a wide array of businesses. We will also avoid behavior that could result in any uncomfortable cash needs at inconvenient times, including financial panics and unprecedented insurance losses.”

Look no further than Berkshire Hathaway's deal with Bank of America in 2011 when it was still dealing with the fallout from the mortgage debt and banking crisis from the Great Recession.

$5 billion was injected into Bank of America — an unprecedented sum from a corporate investor at the time. What came next was unprecedented as well.

What's really wild is the call was routed through the customer service line and rebuffed by a call center representative.

Eventually, he got through. What resulted was one of the most lucrative deals in the wake of a market bloodbath, including $5 billion worth of preferred shares, redeemable at a 5% premium and paying a 5% annual dividend, plus stock warrants granting it the right to buy 700 million of the bank's common shares at $7.14 each.

Buffett exercised that option in August 2017 and more than tripled its money before dividends.

The Berkshire Hathaway position is now worth about $35 billion on paper, accounting for roughly 13% of Bank of America's stock ownership.

Shares are worth over $30 as of March 2023.

We can't negotiate those kinds of terms. What we can do is remember that holding cash and liquid but relatively stable assets like Treasuries creates potential for opportunities when we rather not sell stocks at a loss.

You Need to Know the Value of Dividends

One last lesson we should take from Warren Buffett's commentary in Berkshire Hathaway's 2023 annual letter to shareholders is the value of dividends.

It was even titled “The Secret Sauce,” and the reason is obvious.

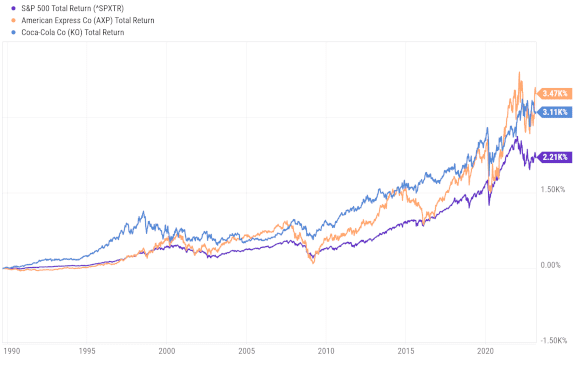

“In August 1994 – yes, 1994 – Berkshire completed its seven-year purchase of the 400 million shares of Coca-Cola we now own. The total cost was $1.3 billion – then a very meaningful sum at Berkshire.

“The cash dividend we received from Coke in 1994 was $75 million. By 2022, the dividend had increased to $704 million. Growth occurred every year, just as certain as birthdays. All Charlie [Munger] and I were required to do was cash Coke's quarterly dividend checks.”

It goes on…

“American Express is much the same story. Berkshire's purchases of Amex were essentially completed in 1995 and, coincidentally, also cost $1.3 billion. Annual dividends received from this investment have grown from $41 million to $302 million.

At year-end, our Coke investment was valued at $25 billion while Amex was recorded at $22 billion. Each holding now accounts for roughly 5% of Berkshire's net worth, akin to its weighting long ago.

Assume, for a moment, I had made a similarly-sized investment mistake in the 1990s, one that flat-lined and simply retained its $1.3 billion value in 2022. (An example would be a high-grade 30-year bond.) That disappointing investment would now represent an insignificant 0.3% of Berkshire's net worth and would be delivering to us an unchanged $80 million or so of annual income.

“The lesson for investors: The weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom. Over time, it takes just a few winners to work wonders. And, yes, it helps to start early and live into your 90s as well.”

Yes, it took many decades, but the compounding effect is dramatic when money is returned to shareholders, even in small amounts, especially consistently over time.

Yet value has been retained in the investment as income has expanded several times over. And, unlike some of Warren Buffett's deals – see Bank of America above – these would have been on par with anyone as long as they owned at least one share.

The scale of investment favors a large company like Berkshire Hathaway or billionaires like Warren Buffett for a lot of opportunities, but that doesn't mean there are none for the rest of us. Dividends and reinvestment in dividend-paying companies are rare equalizers.

Wrapping Up Buffett's Three Big Lessons

Warren Buffett has been investing through Berkshire Hathaway in other companies for nearly 60 years. We need to be honest about how his results cannot be replicated.

His lessons can. Here are three takeaways from his 2023 shareholder letter:

First, you need to recognize when something is not working, especially after you're invested. You need to know why you hold and why you should let go.

Buffett didn't sink more money into his first big acquisition. If anything, he let it wither and die.

The catalyst for profits was simply not there. The cash flow was for a time, and he used that to his advantage. That ties into the second…

You need to keep money on hand for reinvestment elsewhere. The jump from textiles to an insurance company couldn't have been larger. There was no synergy. There was no staff consolidation between the two. It was time to move on, and thankfully Buffett had the money and lending capacity to do it.

Finally, keeping money available for that kind of move matters. That means there is free cash flow. That means money is not tied up.

The revenue growth from investments for Berkshire Hathaway has been the source of its success even when the payoff has been delayed, especially when there is “blood on the streets,” like with Bank of America and American Express.

That money could have gone to other companies in the short term. Investment funds are constantly under pressure for returns, and holding cash and Treasuries isn't impressive to board members and shareholders that want a constant stream of high-margin returns.

Yet, in the long term, they have proven themselves as a fantastic source of long-term returns when carefully deployed.

To recap:

- Know the catalysts for growth and know when to shift new investments elsewhere

- Keep the capacity to reinvest available without the added cost and in a way that can grow over time

- Count on free money flow and consistent returns to shareholders as a source for future investment

Those are the lessons Warren Buffett is trying to impart to investors in his annual shareholder letter when he candidly talks about his past blunders. We'd be fools to ignore him.

Take Care,

Adam English

The Profit Sector