- The Debt Ceiling Is What It Sounds Like

- The Debt Ceiling Is Not What It Sounds Like

- The Investor Implications

- What Should We Expect This Time?

Let's play “hot potato” every couple of years.

Let's codify it in law. Let's offer no prize. Let's burn ourselves time after time.

That is the U.S. government debt ceiling “debate.” The only positive outcome is the status quo. As if that's what we want to fight for…

Does this game sound stupid? Yup.

Are the stakes too high for these kinds of shenanigans? You bet.

Yet here we are once again. The government is already using accounting tricks to cover the political deadlock.

President Biden and Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy are trading barbs and taking positions where neither will budge.

Biden and the Democrats want the ceiling raised with no conditions. McCarthy and the Republicans want to build spending cuts into any legislation that addresses the issue.

We won't bother with politics. We trust you to keep your own. This topic transcends it.

In the hotly contested ranking of things that should never exist, this one is a nearly annual contender. The same goes for the contentious list of misunderstood issues we face as investors.

Let's look at what the U.S. government debt ceiling seems like, what it really is, what happens when Congress fails to increase it, and what it means for us.

The Debt Ceiling Is What It Sounds Like

We should start with something that makes sense. Fair warning, in a minute, we'll rip this apart.

For now, though, the debt ceiling is pretty close to what most people think it is. It's a debt cap, right? Kind of like how a credit card has a limit for spending. In theory, the US government cannot spend more.

That is close to what the debt ceiling is. It isn't a spending cap. It is a cap on new debt issuance.

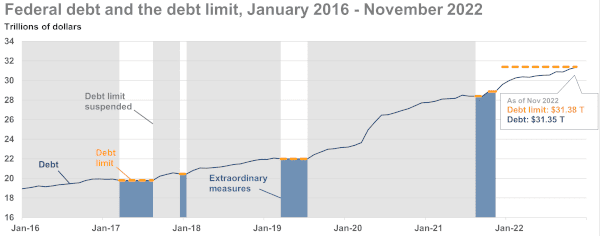

The government isn't done spending. It must fund specific programs and cover the interest on its debts. When the cap is hit, it has some wiggle room – what the Department of the Treasury (DoT from here on out) calls “extraordinary measures.”

It's a euphemism for balance sheet tricks that won't hold up over time.

The DoT starts shifting unused money and obligations between departments to keep a pool of funds available for whatever Congress already demands it spend by law.

Here's a chart from the Brookings Institute that shows how this appears to work out.

The DoT isn't issuing new debt, and it's using money promised elsewhere with a kind of internal IOU whenever this starts.

Since the 1970s this hasn't been an issue. Congress considered the debt ceiling raised when a budget was passed. The rule for this was repealed in 1995, setting up several crises since, first in 1995, as you can imagine, then in 2011, 2013, and now 2023.

The DoT is hardly to blame here. It's doing what our elected officials ask of it.

It's “robbing Peter to pay Paul” if we want to use a phrase dating back many centuries, which – depressingly – shows how long these kinds of accounting tricks have been used.

Contractors and employees often don't get paid, new bonds can't be issued, and the congressional “power of the purse” is curtailed.

So why does Congress act in such a cavalier fashion when it controls both spending and when money can be spent? That's where the whole “credit card” comparison falls apart.

The Debt Ceiling Is Not What It Sounds Like

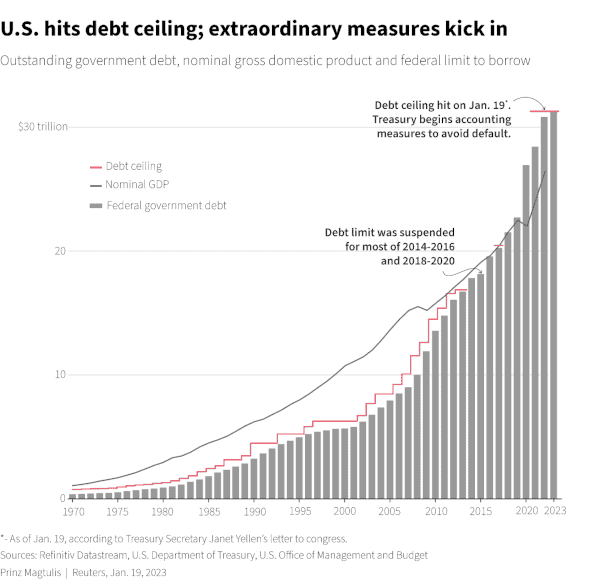

The debt ceiling is hardly static. It has been increased to outpace spending, without fail, since 1917, when the law that imposed it – the Second Liberty Bond Act – was passed.

The real total is in the hundreds over history, but according to the DoT, “since 1960, Congress has acted 78 separate times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit.”

Let's go straight to a chart from Reuters to see what's happening.

Who is raising the limit? Congress! How wildly convenient. Do you both hold a Visa card and are Visa? Does that question seem absurd?

To put it another way, the very people who, by law, are the only ones that can allocate how the U.S. government budgets money are also the only people who can, by law, increase how much they can spend.

Now they are the ones saying they won't cough up all the money they have already spent.

And that is where the credit card analogy completely fails. It exposes the debt ceiling debate as, at best, a tragedy and, at worse, a cynical farce. Regardless, it's a staged show where the two political parties take turns being the aggrieved and the aggressors.

The Investor Implications

The obvious fallout comes with U.S. government bonds. They're a global benchmark. They're a last resort of sorts, where the interest they pay isn't as important as the fact that they always pay. Stability is key.

About two-thirds of U.S. government debt is owned through bonds by domestic investors, both retail – mom-and-pop investors, so to speak – and institutional – U.S.-based investment funds. A lot of international money floods into them, too, but that's not immediately important.

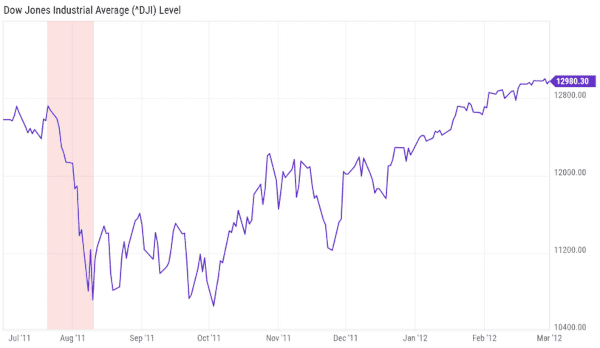

The stock market reacts faster, and it isn't pretty. The debt ceiling crisis in 2011 is a perfect example.

Over eight days in the summer of 2011, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 857 points or 6.7%. The stock market would take half a year to recover.

To make matters worse, Standard & Poor's downgraded the USA's credit rating for the first time in history, rattling the bond market.

What Should We Expect This Time?

Most experts and politicians expect that we will go through the same thing as before. There will be a period of brinksmanship and threats from both sides, and then a deal will pass right at the deadline.

That is cold comfort for investors. Look back at the chart above. The deadline for the 2011 debt ceiling crisis was tentatively July 31. A lot of the stock market drop happened in the week leading up to the deadline.

If the 2023 debt ceiling debate goes right up to the time limit predicted by the DoT we can expect several weeks of steep market losses and increasing volatility in the bond market. With the market bearish enough already, especially after steep losses in 2022, it could take many months, or even years, to recover.

Actually passing the deadline will trigger daily losses that will cause stock market chaos unlike anything we've seen, quite literally since the U.S. has never defaulted on its debt.

It would have immediate and broad economic ramifications too. All government funds would stop. All contracts, benefits, payrolls, etc. It'd start a guaranteed and brutal recession.

As for what sparked the 2011 crisis? That is almost exactly what is happening today. The Republican Party demanded deficit reduction in exchange for lifting the limit. Something it ultimately got.

There are no guarantees, though. With a slim four-vote Republican majority in the House and Democrats in control of the Senate, the potential for a handful of partisan politicians to cause an unprecedented catastrophe is disturbingly high.

For now, the DoT expects it can keep up its “extraordinary measures” until this summer. It's a perfect setup for a repeat of 2011, if not worse. If our elected officials do the right thing and act beforehand, we'll keep the status quo. Nothing to gain yet tons to lose. Let's hope for the best, as underwhelming as it is.

Take care,

Adam English

The Profit Sector